When we last left our Valiant Heroes they were learning of chord Paradigms, specific Progression templates, in a sense, that could be fiddled with.

Now we talked about the most common in terms of overall music, but there are some progressions and paradigms that are just absolutely necessary to be known, and even have their own names(The I-V-vi-iii-IV-I-IV-V kind of bridges this gap a little, being the Pachabel's Cannon progression, as well as being in such songs as Green day's "Time of your life"). Today we're going to learn about two incredibly common Paradigms, with their variations.

The first thing we're going to learn about is the Twelve bar Blues. The classic version of this is very simple, and amazingly famous. In it's most basic form, it is as follows:

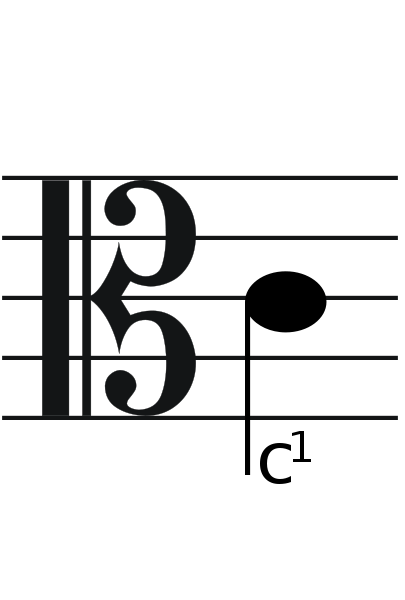

(I'm not sure I covered anything in this fashion before, so here's a brief breakdown on the new notation system I'll be using some of the time. Basically I use vertical dashes: |, to indicate a bar line. I use horizontal dashes: - to indicate beats, if there needs to be differentiation. For instance, if a bar only contains a V chord, it will be written thus: | V | If it contains a V chord on beat one and a IV chord on beat three, it will be written thus: | V IV |. If it contains a V chord on beat one and a IV chord on beat two, it will be written thus: | V IV - - | If there are no dashes, it is assumed that the chords are spaced evenly in the measure)

Twelve bar blues:

I7 | I7 | I7 | I7 | IV7 | IV7 | I7 | I7 | V7 | IV7 | I7 | I7 :| <-(This last bar has a colon indicating a repeat)

It's really as simple as that! It's a little repetitious, yes, but it works. Now, how would we add variations to this progression?

Well the first possible variation is what's known as a Tritone Substitution. This is a huge, huge, huge, huge concept in jazz and related styles. It's also one that is barely ever actually used on the fly, but it's still a big concept. In order to understand the tritone substitution, let's first look at a typical dominant 7th chord. For an example, let's imagine a G7 chord. What are the notes in it? G - B - D - F. Now, between B and F, there's a tritone, which I believe we touched on before. A tritone is an augmented 4th, or a diminished 5th. It is also the interval at the beginning of "Maria" from West Side Story.

Speaking of tritones, let's look at a C#7 chord, a chord with root one tritone away from a G7. In the C#7 chord we have notes: C# - E#(F) - G# - B. This chord, like all Dominant 7th chords, has a tritone in it as well. In fact, while notated differently, it has the same tritone in it as the G7 chord. It stands to reason if you think about it that this would happen. A tritone is exactly 6 half steps in size. An octave contains 12 half steps. Therefore, a tritone is the middle point of the octave. If there is a tritone in a chord, and you move by a tritone, the tritone in the chord will remain the same. So what a Tritone Substitution actually is is swapping out any Dominant 7th chord with the chord with root one tritone away. This gives us some opportunities for some fun with the substitutions.

My next post is going to be a bit of a physics and math talk to explain what I'm about to say, but I want to take a moment to mention that for the most part, the 5th of chords without a modified 5th is the least important note of a chord. Especially with a major third, the 5th is implied through the other notes, and if it's not altered, especially if there's no inversion, the 5th doesn't really add anything to the chord. I mention this now because I'm going to be ignoring the 5th sometimes and I wanted to explain why it's ok.

Now with this in mind, I'm going to demonstrate use of a Tritone substitution in between the I7 and the V7, in G. So we've had 4 measures of G7. Then C7 | C7 | G7 | Now let's say we want a substitution here to lead a little more into the D7 chord. The tritone from G is C#. We're going to throw out the 5th of the C#7 chord for now, so we're dealing with notes C#, F, B. Without the 5th in, we're only altering one note, the 5th of the G7 - D, to the root of the Substitution F#7 - C#. This gives us the same feel as a G7, but with a little more leading.

This is just one example of the uses of Tritone substitution, however. They won't always work, but they can provide a nice sound when they're used right. This is also a really, really easy way to alter the 12-bar blues phrase.

Another way to alter the Twelve bar blues is with passing chromatics. For instance, when going from the V to the IV, we can pass through, either syncopated or not, with a #IV7 chord.

Another very, very simple way to alter the Twelve bar blues is to add a turnaround to the last measure, often ending on a V chord.

Anyways, there was an introduction to both the Twelve Bar Blues Paradigm and the Tritone Substitution. Since Tritone Substitutions are so complex and required such an explanation, I'm going to lightly brush on this next Paradigm relatively quickly.

The next paradigm is a very simple base, that can be used in so, so, so many things.

I - vi - ii - V

On its own it seems pretty innocuous. It's a cute little progression that is pretty happy. However, the variation, the very specific variation that builds off of it, is incredibly, incredibly great. You see, this paradigm is useful in a longer progression which extends it a little:

I vi | ii V | I vi | ii V | I I7 | IV #IVdim | I V | I

Still doesn't quite look like much, does it? Well there's a song you may have heard of:

Hey that's what that song that's super famous! In fact, that progression is used in, like, a million songs. The Flinstones theme even works over it. Now, there's also the bridge, which is just a Falling fifths paradigm starting on the III chord. So it's just:

III7 | VI7 | II7 | V7

Simple as that! The whole song together is AABA, so it's the I-vi-ii-V progression in entirety twice, then the bridge, then the I-vi-ii-V progression again.

Obviously that's just one variation on the I-vi-ii-V, sometimes you don't need any, and there are others. But that's definitely the most famous and useful progression based on the I-vi-ii-V. Also, if you play bass or guitar, Rhythm changes are hilariously easy to voice lead.

Anyways, that's all for our first post back, more to come!

Now we talked about the most common in terms of overall music, but there are some progressions and paradigms that are just absolutely necessary to be known, and even have their own names(The I-V-vi-iii-IV-I-IV-V kind of bridges this gap a little, being the Pachabel's Cannon progression, as well as being in such songs as Green day's "Time of your life"). Today we're going to learn about two incredibly common Paradigms, with their variations.

The first thing we're going to learn about is the Twelve bar Blues. The classic version of this is very simple, and amazingly famous. In it's most basic form, it is as follows:

(I'm not sure I covered anything in this fashion before, so here's a brief breakdown on the new notation system I'll be using some of the time. Basically I use vertical dashes: |, to indicate a bar line. I use horizontal dashes: - to indicate beats, if there needs to be differentiation. For instance, if a bar only contains a V chord, it will be written thus: | V | If it contains a V chord on beat one and a IV chord on beat three, it will be written thus: | V IV |. If it contains a V chord on beat one and a IV chord on beat two, it will be written thus: | V IV - - | If there are no dashes, it is assumed that the chords are spaced evenly in the measure)

Twelve bar blues:

I7 | I7 | I7 | I7 | IV7 | IV7 | I7 | I7 | V7 | IV7 | I7 | I7 :| <-(This last bar has a colon indicating a repeat)

It's really as simple as that! It's a little repetitious, yes, but it works. Now, how would we add variations to this progression?

Well the first possible variation is what's known as a Tritone Substitution. This is a huge, huge, huge, huge concept in jazz and related styles. It's also one that is barely ever actually used on the fly, but it's still a big concept. In order to understand the tritone substitution, let's first look at a typical dominant 7th chord. For an example, let's imagine a G7 chord. What are the notes in it? G - B - D - F. Now, between B and F, there's a tritone, which I believe we touched on before. A tritone is an augmented 4th, or a diminished 5th. It is also the interval at the beginning of "Maria" from West Side Story.

Speaking of tritones, let's look at a C#7 chord, a chord with root one tritone away from a G7. In the C#7 chord we have notes: C# - E#(F) - G# - B. This chord, like all Dominant 7th chords, has a tritone in it as well. In fact, while notated differently, it has the same tritone in it as the G7 chord. It stands to reason if you think about it that this would happen. A tritone is exactly 6 half steps in size. An octave contains 12 half steps. Therefore, a tritone is the middle point of the octave. If there is a tritone in a chord, and you move by a tritone, the tritone in the chord will remain the same. So what a Tritone Substitution actually is is swapping out any Dominant 7th chord with the chord with root one tritone away. This gives us some opportunities for some fun with the substitutions.

My next post is going to be a bit of a physics and math talk to explain what I'm about to say, but I want to take a moment to mention that for the most part, the 5th of chords without a modified 5th is the least important note of a chord. Especially with a major third, the 5th is implied through the other notes, and if it's not altered, especially if there's no inversion, the 5th doesn't really add anything to the chord. I mention this now because I'm going to be ignoring the 5th sometimes and I wanted to explain why it's ok.

Now with this in mind, I'm going to demonstrate use of a Tritone substitution in between the I7 and the V7, in G. So we've had 4 measures of G7. Then C7 | C7 | G7 | Now let's say we want a substitution here to lead a little more into the D7 chord. The tritone from G is C#. We're going to throw out the 5th of the C#7 chord for now, so we're dealing with notes C#, F, B. Without the 5th in, we're only altering one note, the 5th of the G7 - D, to the root of the Substitution F#7 - C#. This gives us the same feel as a G7, but with a little more leading.

This is just one example of the uses of Tritone substitution, however. They won't always work, but they can provide a nice sound when they're used right. This is also a really, really easy way to alter the 12-bar blues phrase.

Another way to alter the Twelve bar blues is with passing chromatics. For instance, when going from the V to the IV, we can pass through, either syncopated or not, with a #IV7 chord.

Another very, very simple way to alter the Twelve bar blues is to add a turnaround to the last measure, often ending on a V chord.

Anyways, there was an introduction to both the Twelve Bar Blues Paradigm and the Tritone Substitution. Since Tritone Substitutions are so complex and required such an explanation, I'm going to lightly brush on this next Paradigm relatively quickly.

The next paradigm is a very simple base, that can be used in so, so, so many things.

I - vi - ii - V

On its own it seems pretty innocuous. It's a cute little progression that is pretty happy. However, the variation, the very specific variation that builds off of it, is incredibly, incredibly great. You see, this paradigm is useful in a longer progression which extends it a little:

I vi | ii V | I vi | ii V | I I7 | IV #IVdim | I V | I

Still doesn't quite look like much, does it? Well there's a song you may have heard of:

Hey that's what that song that's super famous! In fact, that progression is used in, like, a million songs. The Flinstones theme even works over it. Now, there's also the bridge, which is just a Falling fifths paradigm starting on the III chord. So it's just:

III7 | VI7 | II7 | V7

Simple as that! The whole song together is AABA, so it's the I-vi-ii-V progression in entirety twice, then the bridge, then the I-vi-ii-V progression again.

Obviously that's just one variation on the I-vi-ii-V, sometimes you don't need any, and there are others. But that's definitely the most famous and useful progression based on the I-vi-ii-V. Also, if you play bass or guitar, Rhythm changes are hilariously easy to voice lead.

Anyways, that's all for our first post back, more to come!