Ok, I know I said I'd get to chordal tendencies this post, but I'm going to split off a bit to give us some practice in reading and recognizing Roman numeral theory. Also, I'm going to introduce a new concept known as Tonicization, which is essentially playing pretend in a new key. I know, this will feel eerily like homework, but getting practice in this is important, and it'll help cement these ideas. Also, I'll be referencing this example while talking about chord tendencies, since it was originally written just to reinforce that, and then I realized hey, why not get more use out of it.

So, to start, I've written a nice simple, short piece for String Quartet in the key of C Major.

And there it is.

Now, let's a take a look at this piece, since just hearing it doesn't give us too much information:

(Alt Link)

Ok.... eh. That's a little more useful, but that's a bunch of notes in there. If only we just had the chords laid out a little more simply.

(Alt Link)

Ok, there we go. Now, for fun, see if you can figure out the Chords written as absolute notation there(e.g. C, C/E, etc)

Side note: Holy shit, I never taught you guys how to read Alto clef. Fuck, let's do(it live) that now.

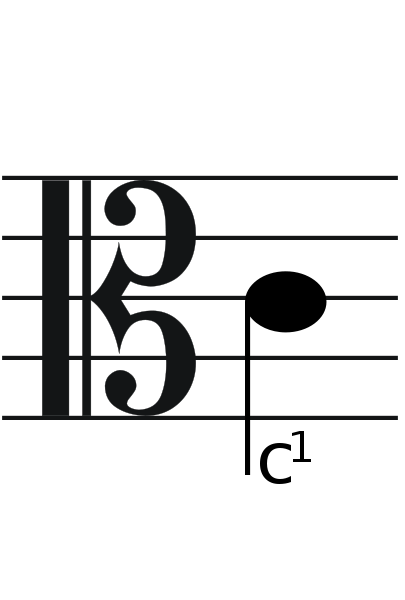

So, those examples have that weird-as-fuck clef thing, don't they?

Yeah, that one.

Well, as that image shows, C is right in the middle of the clef. It says C1 but it's middle C in there. So that's the equivalent of the C one ledger line below the treble clef, and one ledger line above the Bass clef. Why do we use it? Well, you'll notice that the line in those examples pretty much stays in the staff the entire time with that clef. That wouldn't be the case if we were in treble or bass, so we use Alto to make it easier to read. I know, it's sort of a bitch to figure out at first, but if you get used to it, it becomes easier. One thing I like to do to make it easier is to remember that the top line is G, and the bottom line is F. That way, you only have to count from the nearest known note to get to the note, instead of always from C.

Ok, now let's try to figure out the chords in that example. There are suspensions and whatnot, but let's not worry about those, and just focus on the main consonant chord.

It should look something like this(Chords given above the staffs)

(Alt Link)

Note: So I fucked up one of the chords. Anyone spot it? Measure 18, the third measure of the second page. That's actually fucked up in two ways. The first is that I've called it an E chord, which would insinuate E Major, and it's clearly not EMaj. The second is that while in measure 2 we have the same general thing with a C/E chord, in 18 we've got that B in the top line. I wasn't going to give an intro to 7th chords in roman numerals just yet, but hell, looks like I did. So for now, let's say that's a CMaj7/E. Because that's pretty much what it is right now.

Now, let's try to do some Roman numeral analysis shall we? This is pretty simple, right? Take the root of the chord and phrase the number as a roman numeral, so that C chord is a I chord, C/E is.... fuck. I? iii? I/iii? Eh, skip it for now, F is IV, C/G is.... fuck. I? V? I/V? Well goddamn, for writing such a simple example I sure fucked that one up, we can't analyze it! I suck at this music thing.

Note, before I go on, it's important to note that you will often see roman numerals with slashes, such as "I/V". It's very important to note that those are in fact not inversions, but rather a concept I'll get to called "Secondary Dominants"

We introduce two new things here. The first is inversions, the second is a specific type of inversion known as the "Cadential 6-4". So, when we have different bass notes in roman numeral analysis, we phrase them by the intervals in the chord. Technically, a I chord in root position, for instance, is a I5-3 chord. We write them as a fraction(sot of) when we actually write them out, after the number. I can't really explain it better than that here, but you'll see in the example what I mean. This is pretty easy to understand for triads, and a little more confusing with 7th chords.

Triads though, so root position is 5-3, because above the bottom note, we have a fifth and a third. When we go to first inversion(Third in the bass.... That lesson was a while back), then above the bottom note we have a 6th and a 3rd. So we technically would say it's a 6-3 chord. With both of these, though, we don't mention the thirds or the 5ths, because those are... well, they're assumed. Similar to how we don't have to write out "Major" after Major chords, we can just write out "I" and we assume it's in root, or 5-3 position. Now, for second inversion, we do write out everything, which makes it a 6-4 chord.

So with what I've just said, the C/E is a I6, and C/G would theoretically be a I6-4 Chord, right? Well, almost. The C/E is a I6, which is nice and easy, but that C/G is wonky. First, let's cover 7th chords, then we'll go over why we don't in a very specific instance such as the one in the example, call that C/G a I6-4.

So, 7th chord inversions are trickier, because we have three intervals, and three possible inversions. Root is still pretty easy, we just write it as the chord, though it's technically 7-5-3. Now... 1st inversion, let's look at that, 'cause this is where we get stupid. in 1st inversion, we have a 6th, a 5th, and a 3rd. Here, we do write the 5 out. Don't ask me why, but 1st inversion of a 7th chord is 6-5. 2nd Inversion, we have a 6th, 4th, and 3rd. But we just write out the 4th and the 3rd, so 2nd inversion of a 7th chord is 4-3. And finally, Third inversion, with the 7th as the bottom note, We have here a 6th, 4th, and 2nd. We just write out the 4th and 2nd, so it's a 4-2. I've seen something like I2 be written before, but I learned it as I4-2.

For a nice example, look at this site It makes things nice and clear.

Now, I know you're all curious about the C/G, but I know there are probably questions about what I'm going to talk about next, too. So. Look at that example on that site. It's written as I7. But it's a Major 7th chord. So.... what? Well, it's time for another "Fuck Theory" moment. In Roman numeral notation, we assume the unaltered, diatonic form of chords, instead of having different meanings for different 7 writings. So I7 is a Major 7th chord, but V7 is a dominant chord. Confusing? Kind of. Just assume no chromatic alterations unless clearly specified or specific instances in Roman numeral notation. The one obvious exception to this is V in minor, since... well, V has to be modified to be V instead of v in minor.

Ok, and what about that fucking C/G that I've now delayed talking about for so long? Well... this is an example of a specific notation in roman numeral analysis, which we'll see some more of(for instance, It6 chords and the like. Those are assholes too). This is what's known as the Cadential 6-4. It's called that because it's used in a "Cadence"(did I talk about these? Looks like a no. Well shit. Get ready for a long ride)

And what is a cadence, before we explain more the cadential 6-4? Basically, it's the period on the end of a musical sentence. Cadences typically come in 4 main forms, with a bit of sub-forms thown in.

The first is an Authentic Cadence, which is any cadence with a V-I movement. These come in two main sub-forms.

The Perfect Authentic Cadence, which is also the strongest, is V-I in root position, where the highest voice is also the tonic in the final chord.

The Imperfect Authentic Cadence is basically all other Authentic Cadences, including those using a viio or Tritone Substitution in place of a V chord(I know, I know... Tritone subs are waaaay off though, sorry)

The second is the Half Cadence, which is any cadence that ends on V. It's called a half cadence because it's a cadence, but sounds unfinished. It's usually used as part of a repeated or semi-repeated section to indicate the end of the first part, and then replaced with an authentic cadence in the repetition. Mozart fucking loved doing that shit, by the way.

The third is the Plagal Cadence, or Amen Cadence. It's any cadence with a IV-I motion, and it's called the Amen cadence because anytime anyone ever sings an "Amen" in choral music, it'll be a Plagal Cadence unless the composer is a douchebag.

The final is a Deceptive Cadence, which is any cadence that goes from V to something not I. The most common is the V-vi deceptive cadence. Seriously, you see it everywhere.

So. Those are cadences. Now, to the Cadential 6-4. This happens pretty much always over the V chord when it happens(in fact, I'm not sure it could be anything other than over a V chord), and it's a I6-4 chord resolving to a V chord. When writing this, we ignore the fact that technically the I chord is spelled out with notes, and write it as V6-4 going to V5-3. And yes, we write out the 5-3. Sometimes there's a 4-3 suspension in there, so we have to write the 4-3 resolution after the 6-5 resolution, though the 6-4 are written simultaneously. Also sometimes if the composer is feeling super-hamfisted they'll add a 7th after a 6-4 resolution with a 4-3 suspension, and we write that out too. Then we shake our heads and mutter "Hack" under our breath.

Ok, so armed with that information, we can continue looking at the chords as roman numerals in the example, which gets us all the way up to measure 8 before we have another concept I have to introduce. It's almost like this example was written to introduce as many of these concepts as possible in a really clear way.

Anyways, that gets us something that looks a bit like this(Chords above, Roman numerals below):

(Alt-Link)

And if we look past that.... well it starts getting weird. F makes sense, that's just a IV chord, and then... I6? then... ii...V(Major? there's no Bb or natural to tell)....I, well ok that makes sense, but then that leads back to IV? I doesn't feel compelled to go to IV normally. These chords kind of fit in C major, but let's ignore what happened before, and imagine for these 8 measures that we're in F. Now we've got I - V6 - vi - ii - V I - V6 - vi - ii.... II7? Ok, now it stops making sense.

Well, this is a judgment call really. It does sort of make sense in C, but I think it makes more sense in F, because the Descending bass line is a fuck of a lot more common than a descending IV thing. And for this example, let's play pretend we're in F for a few measures.

Well, what we have is basically a tonicization. A Tonicization is really pretending for a small amount of time that we're in a different key, sort of like a key change but without a full key change. The reason we do this is because while it works in both keys in this example, if that gm had a Bb like it should've if I was being smart, then this would've been reeeeeeeally confusing in C, and a lot of times there are chords that are just stupid as hell in the original key that if you think in terms of a different tonic work wonderfully.

Now, when writing out tonicizations, we normally have a pivot chord, which is a chord that works in both keys. In this case, it's that I chord in measure 8, which is V in F. So we add a second line to the analysis that shows us in the new key and continue from there, 'till we get back to the first key. And to go back to the first key, we basically do the same thing, bring back the first line in C on the pivot.

Basically, finishing up the analysis we get the following:

(Alt-link)

Also, you'll notice at the end there I've written "PAC". When we do analysis we like to identify the cadences when they happen, especially at the end. Were I being super-thorough I'd identify all cadences, which would put an HC in measure 4, IAC in 8, PAC in 12, PAC in 16, HC in 20, PAC in 25, and the PAC at the end. And if you're wondering what's with the letters, we basically just abbreviate the names of the cadences. PAC- Perfect Authentic Cadence. HC - Half Cadence, and so on(IAC - Imperfect Authentic Cadence.

Also, were we being super strict about things, we would label all nonharmonics. To give an example, I've done a full-out analysis on the piece, to show what it looks like when you do everything.

(Alt-link)

You'll notice that that's incredible amounts of overkill. We rarely need to go that in depth, but technically we do for a full analysis. The reason we don't is because that's like, useless amounts of information. It's good practice, but that's about it. It's also good to embarass yourself when you write an example for a theory blog originally just for chord analysis and then realize that it's really shittily written in accordance with the rules of voice leading you supposedly know enough about to explain. There are a lot of awful Nonharmonics there that aren't resolved right so.... don't write like that.

Anyways, I think that's enough for this post. Next post, unless I realize there's something else I need to cover before going on will be Chordal tendencies.